For the purpose of learning more about altmetrics and how to use them I collected some quotes from the following journals:

Mendeley Readership Altmetrics for the Social Sciences and Humanities: Research Evaluation and Knowledge Flows by Ehsan Mohammadi and Mike Thelwall. Visualization of Co-Readership Patterns from an Online Reference Management System by Peter Kraker, Christian Schlogl, Kris Jack and Stefanie Lindstaedt.

Mendeley Readership Altmetrics for the Social Sciences and Humanities: Research Evaluation and Knowledge Flows by Ehsan Mohammadi and Mike Thelwall.

“However, citation analysis is restricted to measuring the impact of publications from the author’s perspective, but an article could be useful in other contexts such as teaching, commercialization, and daily working life (Haustein & Siebenlist, 2011; Schloegl & Stock, 2004). In particular, citation metrics are more appropriate for the evaluation of theoretical publications than for applied research. Moreover, there is a worry that a new generation of authors could believe that “citation analysis is a waste of time because authors do not adequately cite those who have influenced their work” (Garfield, 2011, p. 2).”

“Journal usage metrics refer to indicators based on the usage data of electronic journals (Rowlands & Nicholas, 2007) that provide reasonable evaluation of the journals (Hahn & Faulkner, 2002), such as downloads or accesses. Similarly, readership has been defined as “full-text downloads” (Haque & Ginsparg, 2009, p. 2211) or “electronic accesses” of a particular article (Kurtz et al., 2005, p. 111). Usage statistics are able to capture broader research activities (Kurtz & Bollen, 2010, p. 27) and are obtainable earlier (Brody, Harnad, & Carr, 2006) than citation indicators.”

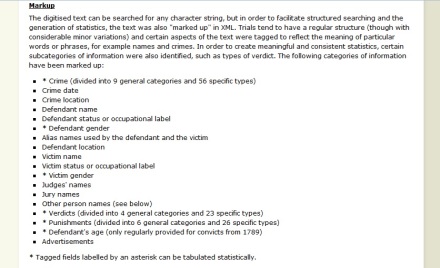

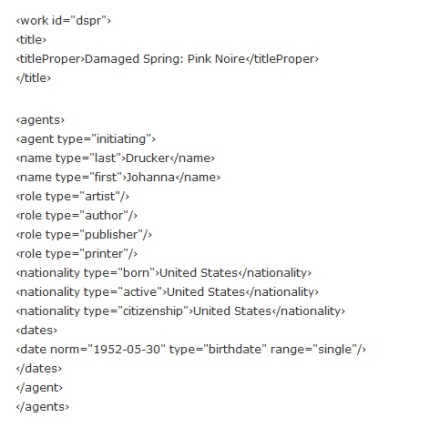

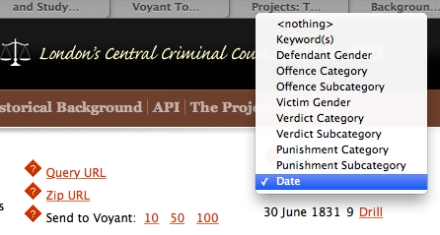

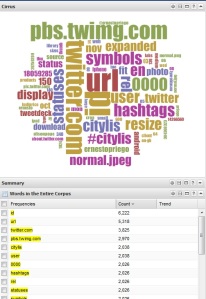

“Data collection for altmetrics can often be based on open applications programming interfaces (APIs; Priem, Piwowar, & Hemminger, 2012), which are faster and more accessible than classical usage data and are easy to integrate (Priem et al., 2011). Among Web 2.0 platforms, social bookmarking tools, such as CiteULike, Connotea, and BibSonomy, may help to overcome the lack of global and publisher-independent usage data (Haustein & Siebenlist, 2011).”

“The present research addresses this issue by assessing whether the relationship between Mendeley readership and citation counts varies across different social sciences and humanities disciplines. Social sciences and humanities studies are not cumulative and topics are not globally agreed in these disciplines (Becher & Trowler, 2001); thus citation analysis has more limitations for measuring the research performance of these areas than for the hard sciences (Nederhof, 2006).”

Visualization of Co-Readership Patterns from an Online Reference Management System by Peter Kraker, Christian Schlogl, Kris Jack and Stefanie Lindstaedt:

“With the advent of e-journals, digital libraries, and web-based archives, click and download data have been suggested as a potential alternative to citations (Kurtz et al., 2005; Rowlands and Nicholas, 2007). Compared to citation data, usage data has the advantage of being available earlier, shortly after the paper has been published. In many instances, usage statistics are also easier to obtain and collect (Bollen et al., 2005; Brody et al., 2006; Haustein and Siebenlist, 2011). Furthermore, usage statistics allow for an analysis of publications and research outputs that do not receive citations or for which citations are not tracked (Priem and Hemminger, 2010).”

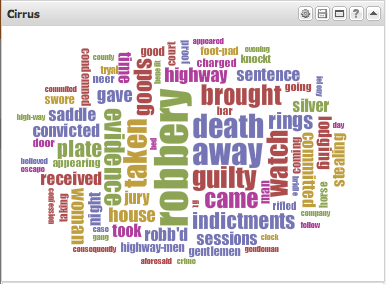

“Therefore, we assume that co-readership can be used as a measure of subject similarity. Co-readership relation between two documents is established when at least one user has added the two documents to his or her user library (see Figure 1). The more often the same two documents have been added to user libraries, the more likely they are of the same or a similar subject. The topical relationship established by co-readership can then be exploited for visualizations by clustering those papers that have high co-readership numbers (see Figure 2). To the best of our knowledge, this measure has not been exploited before for knowledge domain visualization.”

“In social reference management tools we can go beyond mere usage: we are able to inspect the users’ library data. This is an improvement in several regards; _rst, we are able to use library co-occurrence from a single service as a basis for mapping the intellectual structure of a scienti_c domain. Second, being able to precisely attribute papers to individual readers allows for a better understanding of the results. With the help of pro_le information, we can furthermore analyze the inuence of di_erent geographic regions or career stages.”

“An analysis of the results shows that the visualization not free from biases. First, all of the papers are in English, even though educational technology is often researched by local communities that communicate in their native language (Ely, 2008). Second, the knowledge domain visualization represents an education-dominated view that lacks areas related to computer science. Biases in usage statistics analyses were _rst mentioned by Bollen and Sompel (2008) in a study of downloads in an institutional repository. The authors found great di_erences in the correlation of usage impact factor and journal impact factor depending on the user base. The authors therefore concluded that these biases occur due to sample characteristics.”

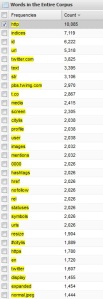

“At _rst, we analysed the geographical distribution of users. One of the reasons for the fact that all of the papers are in English is surely that English is the lingua franca in science and research (Tardy, 2004). But most likely, this dominance of English also stems from the fact that there is a strong bias towards English-speaking countries on Mendeley. This assumption is backed up by the results of the geographical analysis (see Figure 10). Out of 2,153 users, 927 (43.1%) have chosen to list a country in their user pro_le. In total, 70 countries have been named, but the distribution is highly skewed.”